Although Yucatan Back Roads really is all about places to visit around our home state, we may occasionally venture out further into the Mayan world This trip so some sites near Chetumal was fascinating, and also contains some very important information should you choose to travel there!

Let’s start with a couple of maps! This first one just gives you the wide-angle view of where we’re going, from Progreso to Chetumal AQUI MEXICO INICIO” says the big sign on the Malecon — MEXICO BEGINS HERE. Standing on the Malecon, you are looking at Belize.

One note about Chetumal: Their MUSEO DE LA CULTURA MAYA, although it has neither the biggest building nor the largest collection of original artifacts, is absolutely the most beautiful of all the Maya museums we’ve visted–and the displays are totally bilingual. If your travels take you that way, it is not to be missed!

Our route takes the 5-1/2 hour drive down to Chetumal, which is long, boring, and sometimes very dangerous. Then we return via the route we will talk about on this page.

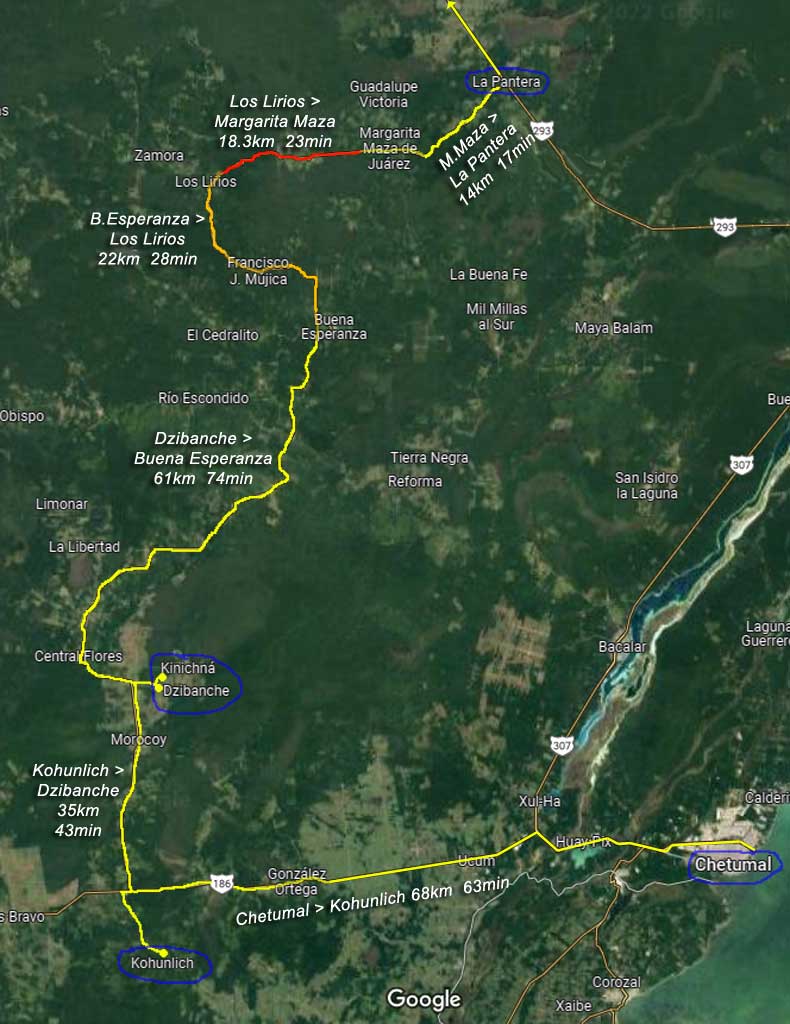

That detailed map is below. The destinations of our journey are the three seldom-visited (but very important!) Maya cities of Kohunlich, Dzibanche, and Kinichná. We had a second goal choosing the route we took, which was to avoid the deathtrap section of the coast highway 307; this is a road with two lanes and wide shoulders, where people pass in the opposing lane regardless of whether there’s oncoming traffic (like you, for example). We far prefer the back roads!

NOTE: The times/distances are from Google Maps; our actual times were similar.

KOHUNLICH

No surprises on the trip to Kohunlich! But the site itself is loaded with them. Start with the most dense jungle we’ve ever experienced on the peninsula. Trees covered with vines, wrapped with trunks of other trees, and one with some strange thing that looked like a pinecone 2 meters high.

Kohunlich dates from 200 B.C.E., but most of the structures were built in the Early Classic period from about 250 to 600 C.E., the Early Classic period. (Most sites in this area are much older than the ones we visit farther north.) It was probably an important site on the trade route from the Chetumal Bay coast to the inland cities of the Rio Bec region like Calakmul, Becán and Balamkú.

Some of the structures are massive platforms, with many rooms and buildings incorporated into one.

There are lots of complex structures, but Kohunlich is best known for its Temple of the Masks. This pyramid has a central stairway that is flanked by huge stucco masks. The Temple was built around 500 C.E., but after 700 C.E., the Maya built another structure over it which protected the masks so they are in pristine condition today! (The huge palapa roof the Mexican government has built over the entire pyramid is there to keep them that way. You can climb the steps and get a very close look.

There’s a lot more you can learn about Kohunlich! We found an amazing Website that we’ll be linking to from now on (and will add to our other pages here at YBR) with detailed stories about dozens of Maya sites. The URL says it all: https://www.themayanruinswebsite.com/kohunlich.html

DZIBANCHE

About 40 minutes north of Kohunlich is the turnoff to Dzibanche and Kinichná, which was a part of that city. There is a roadblock at the turn from the main road; local people are collecting a toll because they say (on a sign in English) INAH gives nothing back to their local community from the visitations to the site. We have no idea what this is really all about, but the 180 pesos (2 people plus the car) is certainly not a problem for us (and we let them keep the change from our MX$200).

You’ve probably never heard of Dzibanche. But this city was probably the origin of the Snake Kings dynasty which created the great glory of the Kaan kingdom of Calakmul. That powerful city-state was the archrival of Tikal to the south, and the two were at war frequently (if not constantly) for hundreds of years. Dzibanche was occupied beginning around 300 B.C.E. and was mostly constructed in the Early Classic period, 250 C.E. to 600 C.E.

(Dzibanche is featured in the National Geographic documentary Megacity of the Maya Warriors. If you can view NatGeo TV’s cable TV channel or subscribe to the streaming service Disney+, take a look!)

The biggest structures are the Temple of the Owl, and the Temple of the Cormorants. Another important structure is named Temple of the Captives, from a carved picture located near the base. (By the way, none of these names, of the cities or the buildings, are Mayan. They were all given by the Spanish, or much later by archaeologists.)

You can see the corbel-arched openings in the sides, and the dark doorway at the top. (The pyramid goes up higher; the next level isn’t visible in the photo.) This is the pyramid that is entered and explored in the NatGeo TV program mentioned above. (It felt good watching the show the day after visiting that exact same place.)

In the Temple of the Cormorants, you can plainly see there were entrances to tombs located deep inside the pyramid.

The photo on the left show (with the arrows) two large masks that look to us like faces of rain god Cha’ak. The square face has a remnant of the upturned nose always found on pictures or carvings of that deity. The photo on the right show just one of the thousands of unrestored buildings that surrounded this central plaza. Laser scans using LIDAR technology show us that there are hundreds of thousands of these covered by jungle throughout the Maya world.

A 3km drive from Dzibanche is Kinichná, which was actually a part of that same city. You go there to see (and maybe climb) one massive pyramid:

There is SO MUCH MORE in all of these sites! Do visit https://www.themayanruinswebsite.com/dzibanche.html for lots of history and more photos! I will be adding more to our Flickr page https://www.flickr.com/photos/yucatanbackroads as well.

THE REST OF THE TRIP

(Refer to the map at the top of the page.) To head back to Merida from Dzibanche, Google Maps recommends going back down to the main east/west highway 186, driving east to Chetumal, and then up the coast highway 307. But they offered a second route up the rural route–about the same time but 60km less distance! We had literally felt our lives were in danger on the stretch of 307 north of Bacalar and were happy to have the rural option.

That turned out to be a big mistake. The road north of Dzibanche had more potholes the farther we went; at one point the meter-wide and 3-meter-long chunk of road had broken off–had that been in the shade and therefore invisible, our trip would have ended right there. At the village of Los Lirios we asked a group of guys which road went to La Pantera (the main highway to Merida); they looked at us like we were nuts, but pointed us the right way.

The photo at right shows one of the best parts of the jeep road (smooth enough to actually aim a camera); most of it was a pair of ruts filled with rocks that definitely threatened our oil pan and tires. Although we never feared for our lives, we were considering the possibility that we would be spending the night in a damaged vehicle hoping for a local on a motorcycle to come by. (Did I mention there is no cell service for miles? There’s no cell service for miles. In fact, at Dzibanché, a member of the staff climbed a pyramid to use her phone.)

This stretch was about 18km and took under a half hour, but it felt like forever, and was exhausting. We arrived at La Pantera with our gas nearly gone (the Range indicator gave us 200km; this driving exhausted it in half that). At that village we made use of information we obtained from a fellow YBR traveler: there is always someone in a remote village who sells gasoline! We asked someone, he pointed across the street, and 5 minutes later we rolled out with 10 liters of Pemex in the tank.

We had already planned to spend the night at Tekax rather than try to make it all the way home, and arrived there just as it was getting dark.

LESSONS LEARNED:

- You can’t always trust Google Maps. (We knew that already, but still tend to have faith in them, especially when the road is shown with a yellow line rather than a thin white one. We always file a correction with Google when we experience something like this; that helps everyone and we hope you do it too!)

- ALWAYS start a trip on unknown roads with a FULL TANK OF GAS. Always. Period.

- When a local looks at you like you’re crazy, you probably are. Remember that a Mexican never wants to disappoint you, and that includes telling you that you need to go back the way you came. (It’s a cultural thing, and really a very nice part of the culture.)

WRAPPING UP

Are we happy we visited these Maya sites? Absolutely! Calakmul gets all the press about this region, but we’ve now seen and climbed some of the buildings in the place where that awesome power originated. We’ve seen enough sites now to appreciate the differences in architecture (like Petén, Rio Pec and Puuc) so these are no longer just big “Ooh, Ahh” rock buildings. Where Chichen Itza gets thousands of visitors a day, a look in the sign-in book shows that these sites get maybe 20 (and this was Saturday). And as it says in our YBR Theme Song:

When the map’s wrong

When the road ends

When we’ve lost our way

We’ve actually done what we set out to do–

We found somewhere new today!